Revenants

Publication for photography exhibit at the Akureyri Museum of Art, December, 2001.

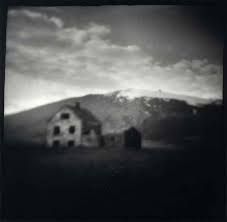

The phantoms suggested by the title of Katrín Elvarsdóttir's series, Revenants, are of a different variety than the spectres that might float through a keyhole. The ghosts glimpsed in her photographs have more to do with things left behind to memory—earthly things, perhaps, but just as haunting. The items or places are inert, yet it is as if they radiate with some last vestige of emotion—a last gasp of imparted spirit. The landscapes, originated on archaic equipment barely more advanced than a pinhole camera, hark back to the earliest era of photography. The territory is of a rural Iceland whose inhabitants have died out or moved on to better prospects, a condition not uncommon to many parts of the world, the cause being anything from industrialization, to climate change. The result is that the environments depicted could be of any high latitude, whether the post-Soviet Union, Labrador, or Patagonia. But because it is Iceland, the ghosts implied within the title are specific to their own culture. The Icelanders themselves may be re-established in Reykjavík or on extended trips around the world. But the folklore remains among the ruins, as if the previous generations left behind a sediment of emotion that has been absorbed into the soil, rendering each outcrop a sentient being. And if the Icelandic interpretation of their mythology is more literal than in other parts of Northern Europe, this would seem a logical enough proposition. Mythology has always fermented in the opaque regions just beyond sight of the campfire, or in the modern era, the zone beyond certifiable evidence. In the effort to maintain an authentic identity within the larger western industrial civilization, a link to superstition has carried over, allowing for a good amount of leeway in retaining a sense of the elves.The land is nameless, the titles of the images not so much documenting specific locations in Iceland as denoting realms no more accessible than the ether of memory.

It is in this way that the parallels exist between Katrín Elvarsdóttir's own origins and her work, as she was born in Ísafjördur in 1964, but her family relocated to Reykjavík. After a period spent abroad during her teens in Sweden, she attended the University of Iceland studying French literature, followed by an extended stay in the U.S., where her inclination shifted to photography. Out of such an environment with so many disparate instincts, Katrín's own personal sensibility resonates with an unflappable integrity. An individual artist with a distinctive body of work, she has functioned and survived within a larger, prevailing global culture, as evident in her shows during the late 1990s in Reykjavík, Florida, Denmark, and New England. Whether in photographs or collage assemblies, her imagery strikes a balance between narrative and a strong graphic instinct.In Revenants, her attention shifts back towards the territory of her origins. She has pared down her technology to the most rudimentary of 120 format cameras, reducing her choices to the essential exposure, the rudimentary optics dictating a unity within the images, with concentric degrees of illumination emphasizing innate distances as palpable and yet indescribable as any glimpse of Elysium or Beulah Land. The result is not unlike an alchemist's camera obscura capturing evidence of a place that is at once just beyond the lens but as inaccessible as the netherworld.It is indeed an ethereal heritage that Katrín has returned home to. Yet for all the prevailing themes that unify the series, there are as many elements that distinguish each individual photograph.

In the photograph "Suðurland II" (2001) the exposure evokes not so much Iceland, but a Soviet Union of secret numbered cities or forgotten gulags. As if in a surreptitious snap taken by an exile, or by remote sensing, the northern sun illuminates what could be either launching gantries or oil wells, the technology reduced by the environment to its most primitive form. And for all the light shining downward, the cold is all encompassing, even while the chimera of the spires would suggest radiation passing through them, rendering everything within the frame lifeless, the dark swath at the bottom of the image not so much earth as inert sediment.

"Norðurland III" (2001) is, of course, more blatant in suggesting a Soviet/post-Soviet venue, as the Cyrillic lettering on the ship's superstructure leaves little doubt as to its origin. The connection between the two worlds would seem logical enough, the shore being on the edge of the abyss, the Arctic beginning just beyond view. Whatever comes from over the horizon, whether Russian freighters, Siberian driftwood, Maersk containers, crates of oranges, or Algerian corsairs, their influences are deposited with the currents, forgotten a month later, but remembered for generations.

"Snæfellsnes" (2001) with its emptied house and connected outbuildings sitting at the foot of a glaciated mountain, the disposition of the sky and the line of the mountain carries a homely trace. As if harking back to the idyll of a silent film epic, the site resembles an archaic redoubt, however the substance, structure, and size of the ruin would indicate a fairly recent past. With its asymmetrical lines and lopsided cavities, the decrepitude is all pervasive — the former occupants having either perished or moved on to a more sustainable existence, as if the region as been formally de-incorporated and declared an empty quarter, abandoned to the hinterlands.

In "Strandir II" (2000) the wreckage of the grounded ship, devoid of any masts or deck structure, righted only by an external framework, has merged with the land and the harbor, forming an inadvertent promontory. The hull, although still solid, would appear to have been picked clean by salvagers, its crew having disembarked more or less in safety to the shore. It is a sight reminiscent of the Falklands Islands and other high-latitude outposts, with generations of working ships beached and written off rather than venture further into treacherous seas. Any sense of memorializing seems happenstance, no plaques being necessary, the long, sculptural lines of the hulk itself serving as enough of a monument.

"Norðurland II" (2001) with its surplus Quonset Hut and mid-sixties Oldsmobile carries over to what now seems as much a mythic era in that it could be called "Middle Cold War." The iconography of both the hut and car scream of a shabby American nostalgia, and unlike the previous images, it is not an abandoned site. The light above the car is on, glowing faintly, and there are no uneven traces of debris in the foreground, just a sparse functionality of the environs. But at most, there would seem to be only a skeleton shift in a workshop, the machinery idling during a summer dusk, the American influences counting as a decorative layer already settling back into the earth.

"Strandir I" (2000) it is not clear if the factory overlooking the span of water, like the previous image, is a derelict or is functioning on some basic level, as a faint wisp of vapor emanating from the chimney appears to mimic the low-hanging cloud in the harbor. But it is the barest sign of life, as the right angles of the building settle into a foreground that is as opaque as volcanic ash – a parked car rendered a faint, half-submerged shape, lost among the murk. With its smudged cement surfaces, worn by time and the elements, it is hard to image the factory ever having supported itself so far on the periphery of any larger economy. Its only apparent link is the water and the narrow causeway and winding road on the right, and yet it might be purely illusionary, as if faces could be glimpsed in the detail as well. All that remains amidst the composition and the interplay of light is that the structure remains, the smokestack still reaching upward, almost a monument, a rust-belt obelisk."

"Að Norðan" (2000) sits under a shroud of overcast, the solitary stucco cottage reflected in a mudpuddle. It could be Ireland or straight out of the remembered potato fields of Günter Grass's Kashubia, and somehow, as if by virtue of its placement within the frame, the cottage evokes a grandmotherly presence, left behind to a hardscrabble existence. It is a sentimental premise, or at least a projected sentiment, as the gulf between the comfortable, reflective present and the earlier generations who tried to make a viable living off such a landscape and often failed continues to haunt as much as any specter.

That "Suðurland I" (2001) should follow "Að Norðan" makes perfect sense, for beyond the link in the weather and the rain-filled puddles, the road winding towards the horizon is no doubt escaping the isolated world of the previous image. There is no sense of arrival, only departure, as if setting off and severing ties is an inevitable fact, but the loss is undeniable. For as much as the landscape is comprehended, having been measured, divided, and worked to exhaustion, it is only upon return that the final aesthetic transformation is apparent.

If arrival is to be had, it is in "Suðurnes" (1999) the overcast of the earlier images having broken, the road having deposited the perspective––in what may belie the title ––to the edge of true North, Ultima Thule, the rough-hewn shrine serving as a marker. As much as it would seem morning, the lateness of the hour––or indeed the epoch–has been reached. It is the fact of the high latitude, the very sense of impossibility that buffets the place with a roar, and that there is indeed a palpable glory cast upon this knoll. It is a glory not dependent on the cross pushed up against the sky; the cross is simply another mythic application, another level of iconography, another visitor's interpretation. The glory is that the patch of windblown high grass and distant mountain frame a rarefied pocket where the transcendent is to be glimpsed, a point where geography and the sublime converge.

Doc Crane, December 2001.

Nightfolk

Which is more frightening– Gothic Genre or a History of the Twentieth Century?

–because compared to the likes of Hitler or Stalin, Dracula might as well have been a quaint, country squire with a few fetishes…

While residing at an Adirondacks hotel in the winter of 1930, the socialite occultist and political intriguer W.A. Richardson surmised the existence of an ancient, preternatural people imbued with pervasive memories and vampiric proclivities. Describing them in his journal as “Travelers,” Richardson would witness the disappearance of Emily, a chambermaid who returns transformed, prompting a calamitous reaction from her husband Jack.

Fifty years later, disenchanted graduate student Fran Avery encounters a still youthful Emily. Drawn into her memories, Fran glimpses a legacy reaching back across the centuries to Medieval Scandinavia——beginning a metamorphosis of her own. Watched over by an aged, seething Jack, Fran contrives to find a way beyond her newfound instincts, her conscience retreating into past experiences and events where she soon gleans the costs of transcendence and redemption.

In the Magical Realist traditions of The Master and Margarita and The Tin Drum, Nightfolk departs from the Gothic genre into the mythic territories of legend and folklore, offering an intimate perspective from within the shadows of history.

Review by Belle Struck– There’s no point in saying that Nightfolk isn’t a vampire novel, but with the exception of one slip of the tongue, the word is never used. The preternatural people at the heart of the story are clearly that, (whether described as “Nättfolk,” or “Travelers,” or even “Nox Viatori,”) but where Ms. Saknusseneouw is offering an expansive and extremely impressionistic historical narrative, vampires with their long lifespans and contagious memories make for a nifty vehicle. Mind you, I’ve never come across any previous nosferatu lore that involved shedding memories, but it’s a flexible metaphor, promising nocturnal locales and predatory glamour, although in Nightfolk the vampires are far less predatory than some of the mortals and movements they come across over the centuries. This is a point made right from the prologue, a journal entry by a boozy old codger named Richardson, whose florid prose style veers between H.G. Wells and H.P. Lovecraft. Sitting out the Depression in an Adirondacks hotel, Richardson sets the story in place, recounting the tale of Emily and Jack, a destitute couple that could be out of a Frank Capra film. When Emily is transformed from a chambermaid into an otherworldly ingénue, her mousy, everyman husband Jack also changes, his puritan instincts curdling with repulsion and desire– turning him into a Paul Bunyan-like recluse.

Transformations abound in Nightfolk. This is clearly where Ms. Saknusseneouw’s fascination lies, for the central character, Fran Avery, is in a process of metamorphosis throughout the novel. Fran starts out a seething upper-middle class WASP who has just ditched her crunchy boyfriend during the summer of 1979. Fran is only too ready to put the liberal seventies behind her. She is craving reaction if not outright tyranny, her instincts aligning with Sylvia Plath’s lament of “women adore a Fascist.”

So when Fran meets a still very-young Emily, and is lured into her universe with it’s invasive memories, she will indeed get to meet Fascists, among them Jack. One can picture Fran evolving into a kind of Ann Coulter if she made it into the Reagan Era–if she stayed on in what the novel calls “the Natural World.” But upon being transformed, Fran passes through a succession of memories and consciences, effectively becoming a time traveler. Along the way, Fran finds a conscience of her own, and tries to forestall morphing any further by becoming a Rip van Winkle.

During her long, long sleep, she glimpses a number of periods, some iconic, such as the French Revolution and the London Blitz, other eras are obscure, involving long-forgotten revolutions, pogroms, and cocktail parties– with the Nightfolk forever watching from the sidelines. A few of the Nightfolk that Fran encounters are indeed quite dangerous, while others are discreetly hapless, or have simply seen too much. More often it’s the mortals of the daylight hours who are out of control, especially Emily’s ancient husband Jack, whose crazed pursuit of redemption over the years assumes monstrous proportions. Jack is a complicated fellow. He starts fires, fights fires, and then embraces a homegrown Fascist group in the early ‘30s only to kill hundreds of Germans when war comes. As hard as Jack tries to purge himself, he can never shake off his attraction for Emily– a fact that Richardson, even as a ghost, repeatedly teases him about.

History, for Ms. Saknusseneouw, seems to be an ongoing process of waking up a relic, no longer relevant, while the people who have stayed on have changed beyond recognition, possessed by events, ideologies, and misguided piety.

The result is a web of mythic tangents, as Nightfolk plays out like a dreamy labyrinth– making for a rather cracked morality tale.

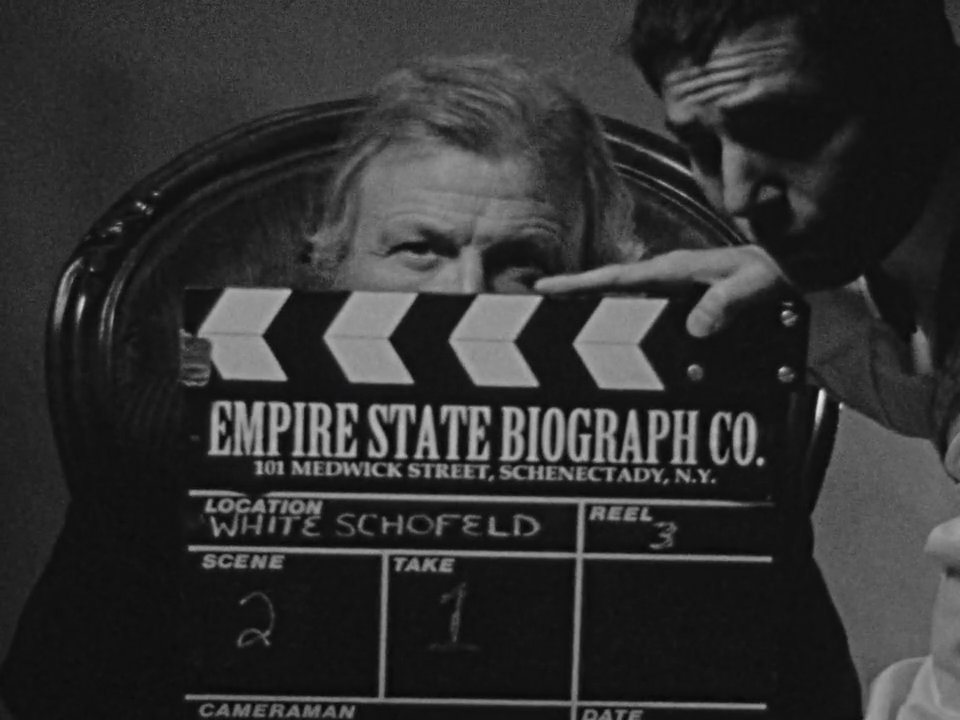

On January 5, 1931, the socialite occultist and political intriguer W. Arthur Richardson sat down for a newsreel interview. It would be the last public record he would offer, drawing from a diary that forms the beginning of NIGHTFOLK.

Tales of the New English

Tales of the New English was a feature film project shot between April 1984 and March 1988.

Set in 1677 Plymouth Colony in the aftermath of King Phillip's War, the story follows the travels of Isaac Harlowe, a destitute farmer's son from the Outer Cape, and Rupert Greenwich, an aristocrat sent from London to investgate the whereabouts of a Regicide--one of the Puritan Judges who condemned Charles I after the English Civil War.

Determined to "better his prospects," Isaac Harlowe leaves his family's impoverished farm in Eastham to seek out his uncle in Scituate, Sebastian Entwistle, a wealthy merchant with suspected Royalist connections.

Matt Fallon as Isaac Harlowe (right) and Bill Barnard as Sebastian Entwistle

By the 1670s, Scituate was the wealthiest town in Plymouth Colony, its economy dominated by a handful of shipowners and merchants known as "The Men of Kent." One of them is Sebastian Entwistle, whose worldly Dutch and English trading connections and presumed Royalist sympathies, is viewed with suspicion by the Puritan authorities. And when the war forces inland settlers to take refuge in the port towns, Entwistle fears that the hysteria will turn towards him, and so he fills his household with displaced relatives, taking in Isaac as well.

Each town in Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth Colony was organized around a Puritan "Covenant," as their parishes were called. Each member had a designated role and position within a well-defined hierarchy. At the head of each covenant was a minister, and when the inland towns were abandoned during King Philip's War the remnants of their covenants regrouped in towns like Scituate, where their squabbling ministers formed an inquisitional "Committee."

Paul Boynton, Mario Giammarco as Reverend Ottershaw, Jeff Ginsburg, and Mark Rogers as Reverend Hammett.

Matt Fallon in a later Incarnation.

Monika Anderson and Gretchen Hopkins.

Gretchen Hopkins as Penelope, daughter of the Regicide Oliver Frye, and Tom Shillue, as a later incarnation of Isaac Harlowe.

David Prifti and Dennis Conway.

John Franklin as Mungo Macdonald.

Scottish Highlanders were brought to New England as prisoners captured after various uprisings during the 17h century. In the episode "The Papists" the newly arrived Scot attempts to escape, only to be talked down from a tree by one of the ministers Irish servants. Unknown to the ministers, the Irish Servant, Martin, is actually a Catholic Priest who tends a secret parish. This storyline was drawn from the historical precedent of a Jesuit who was discovered ministering to an underground church in Hingham in 1668.

Bob Deveau as Ensign Harry Foxe, the leader of the Militia Column sent from Scituate to recover settlers from towns abandoned during the war.

Group Shot. Tucker Stilley as Juno Finch, Bob Deveau as Ensign Foxe, Larry Blamire as Lloyd Mercer, Eric Robinson as Ian Chandler, Bill Barnum as Job Kendrick the Pedlar, Ken Skeer as the Baliff, Andy Giammarco as John Buttons, Matt Fallon as Isaac Harlowe, and Doc Crane.

Matt Fallon, Tucker Stilley, Andy Giammarco, Larry Blamire, and Bob Deveau.

Andy Giammarco as John Buttons.

Susi Alloush as a later incarnation of Penelope Frye.

Margit Baldemair as Goody Hallett.

Bob Moussavi and Gretchen Hopkins.

Shadows of June

How can we see without eyes?

In 1919, the White Russian Princess Katerina Georgievna was ransomed and secreted to a remote farmstead in the Wachusett Forest. Betrothed to the political intriguer A.A.Richardson, the wedding never took place, and the Princess soon afterwards disappeared––the incident lost to the historic record.

As an experimental project shot in 8mm negative by the Cambridge staff of then-Super8 Sound, the film was an initial test of the pre-market 50 and 500 ASA film-stocks as well the just-released Steadicam JR system.

February 17, 1919

My Dearest Sir,

H.H. Katerina Georgievna has been sent from her reclusion in Sweden to a new location that must remain undisclosed for her future safety, as she is one of the few remaining descendants of the First Czar Nicholas. An intermediary, Mr. Epstein has been dispatched from Boston City to serve as translator and negotiator regarding the terms of her engagement.

Please understand that Mr. A. Arthur Richardson has gone to great expense to secure her release from the Insurrectionists, making sure that her passage incognito on the S.S. Dumonia was as comfortable as circumstances would allow. He is a man of great generosity, but you must understand he reserves the right to negate the betrothal if her titles, honors, and dignities are not ultimately assigned to him.

If that proves to be his decision, arrangements will need to be made for her dispensation at a later date, to be determined by Mr. Richardson.

Most Sincerely,

Jens Ulbricht Mogenssen

June 2, 1919

My Dearest Sir,

Mr. Epstein has informed me that on the 30th of May he traveled to the location where Katerina Georgievna is secluded. He states that the residence is far more rustic than one would expect for someone of her position, with no official retainers, and only one servant to cook and a bodyguard tasked as a groundskeeper. According to Epstein, a great informality has transpired, as the princess left instructions for him to be received not in the hall of the Manse, but in a meadow that she now frequents. Although her bodyguard Captain Wilmar has described the princess as melancholy and given to long walks in the forests that surround the sanctuary, Epstein states that he was graciously received and was offered far more courtesy than someone of his station would expect.

Please refer to the photographs provided by Captain Wilmar, as per Mr. Richardson’s request regarding the conduct of Epstein’s audience with the Princess.

Most Sincerely,

Jens Ulbricht Mogenssen

June 15, 1919

My Dearest Sir,

Mr. Epstein has reported that he has had a second and third visit with the Princess Nina Katerina Georgievna and they have extended discussions regarding the details of her wedding to Mr. Richardson. Because of the danger posed by Bolshevists keeping watch on public venues, the arrangement had been to use the Roman Chapel once used by the estate’s Irish servants. The Princess has asked for an Orthodox prelate to perform the Russian rituals, although there has been some difficulty determining whether the chapel will be suitable, or whether a Russian cleric can be obtained, as none so far have been willing to communicate with Epstein.

Otherwise a tentative date has been suggested, pending word from Mr. Richardson, who is currently in Habanna, and has still has not indicated if he will agree to anything other than an Episcopal service.

Most Sincerely,

Jens Ulbricht Mogenssen

June 23, 1919

My Dearest Sir,

A date has been set. I have received word from Mr. Richardson that he has agreed to the terms Mr. Epstein negotiated with H.H. Katerina Georgievna and that he will arrive on July 1st for a wedding service within the Roman chapel. Apparently Mr. Richardson has located an ordained Russian Orthodox cleric in Newark who is willing to perform the rituals. The Princess is to depart with Mr. Richardson to his family estate on the Hudson on the same day. Mr. Richardson is satisfied with the title of Count, although the domains he has been granted are at present still controlled by Latvian freikorps.

Captain Wilmar is reported to be having private communications with Mr. Richardson regarding the rapport observed between Mr. Epstein and the Princess, and it has been suggested by Mr. Richardson that given Mr. Epstein’s excellent references and services rendered, he should now be sent to negotiate with the Latvians.

Most Sincerely,

Jens Ulbricht Mogenssen

July 18, 1919

My Dearest Sir,

I regret to inform you that no wedding has transpired between Nina Katerina Georgievna and Mr. Richardson.

The Princess waited at the Roman chapel as agreed on the morning of July 1st, however is was not until the Ninth of the month that word arrived of Mr. Richardson’s marriage in the Adirondacks to the motion picture actress Madge Kimball. We have received no word from Mr. Richardson regarding any dispensation or arrangements on behalf of the Princess, and Captain Wilmar has apparently left the estate on the day his salary ended. Mr. Epstein has inquired on behalf of the Princess, and I am at a loss as to how best to advise him. Please contact me and advise whether she should be returned to Europe or if the are any other contacts who can offer her safe passage.

Most Sincerely,

Jens Ulbricht Mogenssen

September 3, 1919

My Dearest Sir,

I received word from Mr. Epstein that he traveled to the estate in the Wachusett Forest where Katerina Georgievna had been in seclusion, but was unable to locate her. It is not clear if whether she left on her own or if she has been taken by Bolshevists, given the circumstances of Captain Wilmar’s recent death. The housekeeper has taken up a new position and has sent Mr. Epstein a telegram believing that the Princess is still on the grounds, and waiting for word from her family.

In any event, our agency has concluded it arrangements with the White Russian Legation and Mr. Epstein is no longer in our employ. Please be informed that our New York office has initiated legal action against Mr. A. Arthur Richardson on several counts, and we offer you our counsel should you desire to co-litigate.

Most Sincerely,

Jens Ulbricht Mogenssen

How can we see without eyes?

hear without ears?

feel without fingers or a heart?

How can we remember when there is nothing left–

When history itself has forgotten,

is the soul left blind and deaf,

alone in the dark?

For those who come after,

who see a sun in a different part of sky,

who experience what we could scarcely imagine,

we are of different realms, separated by a gulf of years.

And yet…

The Grand Old Man

Playing Santa Claus is no small thing. Never mind the current image of some shabby old man reeking of booze with a five o'clock shadow visible beneath his strapped-on beard. Where I came from just west of Boston, the question of who would represent Saint Nicholas was taken very seriously.

Originally in old Framingham, there was only one department store that had a Santa Claus, Kerwyn's, which was just across from the Kendall Hotel. That was in the twenties. In those days, when the only practical way to Boston or Worcester was by the New York Central railroad, most people stayed in downtown Framingham to do their shopping. Kerwyn's was the premiere establishment, and they went to great lengths to make sure that their Christmas displays matched in splendor if not in scale anything that Filene's or Jordan Marsh put on. To that end, they were very careful about who they had for Santa Claus. It had to be someone of impeccable reputation and authority, and so for many years they had Octave Kellogg, a retired instructor of geography and rhetoric at the Framingham Academy. Even then, the old Academy was considered a thing from the venerable past, having been replaced just after the World War by a modern high school downtown. For with far more Irish and Italians downtown than Yankees uptown, even the name Octave Kellogg harked back to the kind of ancient Saxon Christmases depicted by Currier & Ives. Sitting in his high-backed chair, addressing the children and grandchildren of his former students with all the commanding dignity and grandiloquence of an Old Testament Prophet, Kellogg of Kerwyn's was by all accounts the quintessential Saint Nicholas, becoming the benchmark by which all future Santas would be judged.

So as Framingham and the towns around it changed, new approaches befitting the times were tried. By the fifties, when the new Shopper's World up on Route Nine became the first shopping mall on the East Coast, Kerwyn's and all the other downtown businesses began their long decline. With branch stores like Jordan Marsh coming out from Boston, and Santa landing by helicopter with Rex Trailer in the open-air courtyard, there was no competition. Santa Claus had entered the Modern Age. Each new mall had its own Jolly old fellow, some approaching their craft with the gentleness of Captain Kangaroo, others going about it more gregariously; such as the bus driver, Frankie Fonacari, who occasionally burst into carols with a hearty baritone voice. To the managers of the Natick Mall, Fonacari was a dream come true, for when the line of waiting children and parents grew longer and longer, and tempers frayed, he had a cat's sense of when to start the crowd along on another round of carols.

With such a history then, what happened at The Fells Crossing last year should be kept in perspective. Only open for five years now, The Fells, by its location on Route Nine in the more upscale town of Wellesley, was inevitably going to be very different from the mainstream malls and outlet centers in Framingham or even the sleek new Natick Collection. In its design and size, The Fells is far more reminiscent of the very exclusive Atrium in Chestnut Hill, with three levels of posh shops surrounding a skylight-covered court. Two intricately crafted sets of Edwardian glass elevators rise up and down at both ends; while in a special alcove on the lower level, there are not one but three pianos that have been positioned by a special consultant for the best acoustical results. On Friday and Saturday nights throughout the year, the pianos play a repertory ranging from light classical to Cole Porter. But from Thanksgiving to Christmas, the three pianos play all manner of holiday tunes for four hours every night.

It is therefore no surprise that The Fells Crossing was just as meticulous in selecting a Santa Claus. At first there had been some discussion among the management whether it was appropriate for The Fells to even have one- but when it was decided, they held a very careful screening process. Their choice would have pleased Octave Kellogg himself, as they found Santa Claus in the person of Shepard MacKenzie.

MacKenzie, who pronounced his English in round cadences that suggested Orson Welles, had once trained with the Royal Shakespeare Company in London and was a longtime fixture of the Boston theater world, having taught for ten years at Emerson. To the humbled children sitting in his lap full of awe at his regal benevolence, MacKenzie was a palpable Saint Nicholas, if not Jehovah himself. For children who had long since grown cynical about all the versions available, he was a powerful reminder of things past, having acknowledged in one interview with the Metro-West News that he had modeled his Saint Nicholas on equal parts of Falstaff and King Lear.

For the management of The Fells, MacKenzie's on-going interpretation fit the profile of their mall to a tee. While the other malls had a Santa in a regular Santa suit, the lot of them looking like overweight gnomes, The Fells Santa Claus had outfitted himself with the long-flowing robes of an English Father Christmas. With MacKenzie, each evening was a performance in itself, not least of which was the in-house Christmas party, where by the third Christmas, he recited from King Lear while in his majestic robes. In a brief five-minute performance, which, with all the champagne punch, moved very quickly, MacKenzie's Santa Lear asked which one of his three elves loved him the most. That year the elves were English Literature majors from Regis College, and having playfully rehearsed the scene beforehand, they made for a heady performance that stirred the throng of managers and seasonal help into a tipsy roar of "Encore! Encore!" Even the otherwise reserved English manager of the Crabtree & Evelyn shop remarked it was some of the best fringe theater she had ever seen.

So on the fourth year, with the holiday season moving along hectically into the second week of December, it came as a shock to everyone at The Fells when Shepard MacKenzie vanished. The Regis elves were the first to notice his absence, arriving to work in costume at the designated time, only to find MacKenzie's Second Empire throne chair empty. After waiting awkwardly for fifteen minutes with a small crowd gathering, the manager called MacKenzie's home number. There was no answer. Not even MacKenzie's usual answering machine with its passage of Falstaff from Henry IV part II clicked on. Just ringing. It was not like MacKenzie; he had once berated an elf for being ten minutes late, bellowing for all in the parking garage to hear that punctuality was as important as presentation.

As it settled in that something was very wrong, all parties at The Fells started getting very nervous. MacKenzie's elaborate rendition was now a major attraction, and on this night a television crew scheduled to arrive at peak hour. The Executive Manager's otherwise staid office flew into a panic. What were they going to do? There was no question about bringing in a regular Santa; it couldn't be someone with a fake beard in the short jacket and boots– the disappointment on the crowd's faces would be broadcast live all over Boston.

Five administrative assistants in the main office frantically tried to track down MacKenzie. One of the assistant managers even drove down Route Nine towards his house in Newton, thinking they might find him with his car broken down. But there was no sign. MacKenzie had vanished.

Finally they were able to reach Nelson Burke, whose name was listed as a reference on MacKenzie's original application form. Burke, like MacKenzie, was a regular in Boston theater world. He was about the same age, and also like MacKenzie, he was known as a "King Player." He had no idea what could have happened to MacKenzie. They had kept in regular contact, and as if to confirm the main office's panic and dread, he agreed it just wasn't like MacKenzie to disappear. While the Executive Manager of The Fells shouted in the background that the news crew was on its way, the woman speaking to Burke hurriedly asked about what he did and if he could help.

To ask an actor – especially a King actor – what they do is a loaded proposition. Burke immediately started effusing about the one-man show he was pitching to the Turtle Lane Playhouse, concluding his spiel as he had a dozen times that week, "Now there was a grand old man, absolutely magnificent!"

With all the shouting going on behind the administrative assistant at that moment, it was never made clear what exactly she heard, only that there was a complete miscommunication between her and Burke as he carried on over the phone, and that she did say the words, "Fine, Yes, and Come." The context, however, is still being disputed.

Burke rushed over to The Fells, arriving just as the WBZ News crew was unloading its van. Burke, like MacKenzie, believed that the entrance to any scene is all-important. So in grand style he rolled out of the ornate glass and copper Edwardian elevator straight into the throng of waiting parents and children as none other than Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Gliding along in his wheelchair, with a velour navy cape over his shoulders, fedora titled slightly, and cigarette-holder at a characteristically jaunty angle, Burke took his position. Without hesitation, the very hard-pressed Regis College elves, who this year happened to be history majors, immediately played along, moving children directly into the Grand Old Man's lap. A second later the television crews turned their lights on, instinctively finding their way to the best angle. While Burke played to crowds and the camera, one of the cameramen whispered to another that he felt as if he were shooting newsreels. All of them felt the presence of the old Roosevelt magic.

For the managers of The Fells watching the proceedings as they were being televised live, it was a moment of stricken horror. Their faces stretching into a painful wince, they didn't notice that the crowd simply took it to be a new attraction. Watching numbly, the managers didn't even object when one of the elves cued the piano trio to play "Happy Days are Here Again" as well as the theme from "Annie."

As the television crew came towards the cluster of managers for an on-air comment, one of them muttered to the other about what to say. It didn't occur to the Executive Manager that even he at that moment was quoting FDR when he whispered to them, "Whatever happens, just tell them you planned it that way."

But that was the way it went that night, Burke had researched and rehearsed Roosevelt for so long that he could charm away any question that even the most uninitiated or disagreeable children could pose. If a toddler asked for a GI Joe doll or a GoBot, he would respond with a chuckle that would put Ralph Bellamy to shame– assuring the boy or girl that he would see what General Patton or Doctor Einstein could come up with. When a little girl asked for a puppy, he told her all about Fala. When another chided him for smoking, he responded that that was why he had the holder, as his doctor had told him to keep cigarettes as far away from him as possible.

There was a crowd of waiting children and adults right up until closing time. Staying on for an eleven-o'clock spot as well, the producer with the television crew spotted Chaz Packenham, the very patrician State Senator from Dover in line with his grandson. As the lights were aimed on him and the questions were posed, Packenham voiced no objection to mixing Roosevelt with Christmas. "Well, after all…" the Senator said through his own slightly locked jaw, "That Man was very good at giving things away…"

Any further ironies about Wellesley once having been a bastion of Roosevelt-haters were just as easily dismissed; apparently all that had been smoothed out over the years. It didn't even matter that he was supposed to have been dead for over half a century, as one precocious nine-year-old pointed out; for old Father Roosevelt had an answer or at least a good retort for everything.

Over the next week, the crowds kept on coming. With the original television report having been picked up and re-broadcast as far afield as New York and Washington, a number of national and foreign news organizations made their way up to cover it, the sensation even finding its way to several political commentary columns.

The shops on all three levels reported their businesses were doing very well, and they were generally satisfied with the influx of new clientele, even though many of them were from traditionally Democratic districts. And so with the incident turning out favorably, the managers of The Fells drew a sigh of relief, convincing themselves that having FDR sitting in for Santa was just urbane enough a concept to fit the persona of their mall. Burke was signed to perform straight through to Christmas and was an equally big hit at that year's Christmas party.

Officially, no one ever found out what happened to MacKenzie, just that he had picked up everything in his house and left with no forwarding address. Whether or not he was trying to get out of his contract was never confirmed; however, there were several rumored sightings of a man on television with a very aristocratic white goatee holding court in a marmalade commercial.

This year Burke was approached to play Roosevelt again, but then before a contract could be signed, everything was put on hold. Word has it from one of the Regis Students now working in the office that an assistant manager floated the idea of trying out a Teddy Roosevelt as well. It seemed to everyone like a possibility, but when they started discussing the idea involving other presidents, including having a Harry Truman play one of the pianos while Burke did FDR, it all came to a halt when they thought of kids sitting in the laps of either Nixon or Clinton impersonators. For when it occurred to them that it might resemble a Hall of Presidents, the Executive Manager ended the discussion, insisting that they were overseeing The Fells Crossing in Wellesley, not Disneyland. No one brought it up in the office again.